And now a few words about quarks. While many are familiar with word itself, I suspect that few actually really know what a quark is or how it relates (if at all) to the world around us. Since I’m quite interested in quarks (one quark in particular), I thought it useful to discuss them.

Our bodies and the materials we see around us are made up of molecules (or chains of molecules). Molecules are groups of atoms that are stuck together. Atoms are protons, neutrons, and electrons that are stuck together. Every neutral atom has the same number of protons and electrons, and atoms are named by their number of protons (1 proton = hydrogen, 2 protons = helium, etc). Atoms can have different numbers of neutrons, and these are called isotopes.

So, where does a quark fit in? It turns out that both protons and neutrons can be decomposed into smaller particles, called quarks. Protons and neutrons are just groups of quarks, just as molecules are groups of atoms, etc. Specifically, protons and neutrons are made from two quarks: the “up” quark and the “down” quark. A proton is two up quarks and a down quark, and a neutron is an up quark and two down quarks ( Proton = uud, Neutron = udd).

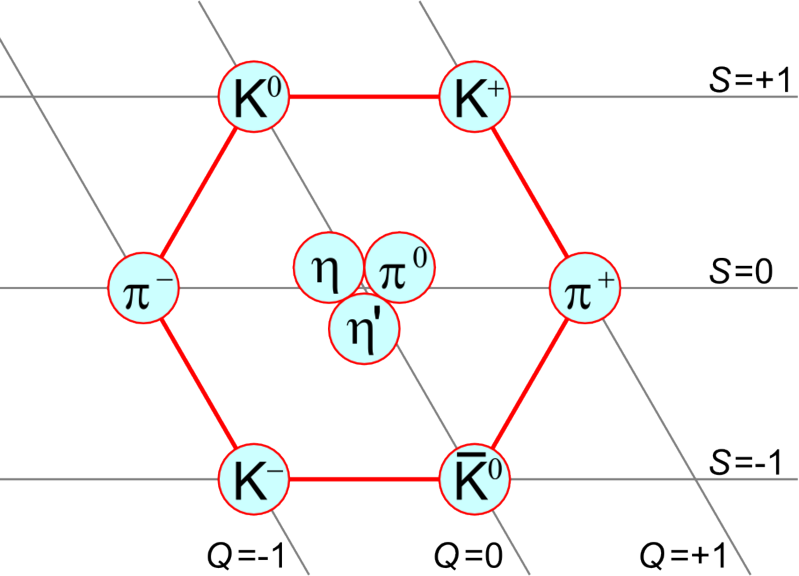

So, how do we know this, or why would we think that these things called protons and neutrons are made of other things called quarks? It turns out that quarks make a lot of seemingly disconnected phenomena make a lot of sense. In addition to the (somewhat) familiar protons and neutrons, scientists have observed a large number of other funny particles. These particles can be seen when we smash things together in colliders, or when things smash into our atmosphere, or when things radioactively decay. They include funny sounding things, such as “pions,” “kaons,” the “eta meson” and many others. Scientists observed these particles but initially had little understanding of why they existed or how they related to each other. They were seemingly a random grab-bag of odd objects.

However, several brilliant people noticed that there were patterns with these particles. It you take these particles and look at their charges and spins (fundamental properties that describe all particles), you’ll see that they fall nicely into shapes and patterns. These patterns suggest that there is some common, underlying structure to these particles, and that different particles are simply different possible manifestations of this structure.

The model of quarks was designed in the 70s to explain this structure. At first, scientists introduced three quarks (the up, down, and “strange” quark) and invented a theory that described how these quarks interact (Quantum Chromodynamics, or QCD for short). Using this theory, which is essentially a specific application of group theory, theorists were able to show that these three quarks mix together to form the strange menu of particles that were observed. Incidentally, the name quark comes from none other than Joyce:

Three quarks for Muster Mark! Sure he has not got much of a bark And sure any he has it's all beside the mark. —James Joyce, Finnegans Wake

Some people didn’t accept this theory at first. And then, something remarkable happened. Scientists at the Stanford Linear Accelerator (a particle collider that, unlike the LHC, is linear instead of circular) noticed that there was underlying structure to quarks, that they were made of smaller, more fundamental particles. It is somewhat miraculous that an esoteric theory of quarks that started out as a thought experiment in group theory was perfectly suitable to explain these newly found objects.

Moreover, as time went on, even more particles were found, which essentially led to the discovery of even more quarks. If you add another quark to the initial group of three, your theory will predict a wide range of new particles. And indeed, particles were observed with the exact properties predicted by this addition of this new quark, which is remarkably beautiful evidence for this theory’s correctness. This new quark was called the “charm” quark, and soon after another quark, the “bottom” quark was discovered as well.

At this point, sometime in the late 70s, 5 quarks had been discovered, and they were grouped together in pairs based on their properties: up-down, charm-strange, and the bottom quark, which was left without a partner. At this time, scientists predicted that they would discover a partner to go with the bottom quark: the so-called “top” quark. It wasn’t until 1995 that this quark was eventually found. The top is unique among the quarks for various reasons and has a very interesting role to play in modern physics, which is why scientists at the LHC are so interested in studying it.