Last year, Google's DeepMind team (a team dedicated to machine learning and artificial intelligence research) announced that they had built a new neural network based model, known as AlphaGo, that was designed to play the ancient game of Go. Their model made headlines as it boasted a proficiency at the game past any human expert and then justified that claim by handedly beating some of the top players in the game.

Recently, DeepMind has released an update to their Go playing AI, dubbed AlphaGo Zero, which is impressive not only in its improvements over the original model's proficiency at Go, but also in the way that it achieved that proficiency.

The original AlphaGo was an AI based on neural network / deep learning techniques and leveraged novel reinforcement learning tactics. It was built in part using data from many human-vs-human games of Go, which it used to learn how to play the game. Once it had learned enough from these games to play competently, AlphaGo was programmed to play against itself many times, generating more data. Later versions of AlphaGo were trained on that additional data to bootstrap their knowledge of the game, learning from the mistakes of previous iterations of itself.

Unlike the original version, AlphaGo Zero was never shown human-vs-human games for training. Instead, its knowledge of Go was generated initially by randomly playing against itself, learning the game only by being told which side won after playing randomly. It then bootstrapped its own knowledge by studying the games of its previous generations performing "self play", effectively bootstrapping its own knowledge from scratch.

AlphaGo Zero's success using this technique his profound implications. The fact that an AI can teach itself such a complicated from scratch opens up the door for applications to many other games or problems where an existing corpus of data doesn't yet exist. It shows that a well-guided neural network can become world class only by being told whether it has won a game or lost after playing it through to completion.

Inspired by this idea, I wanted put together a demonstration of AI bootstrapping myself. To do so, I applied the techniques of AlphaGo Zero to the much simpler game of ConnectFour. Similar to Go, ConnectFour is a game played by placing colored tokens on a board. In ConnectFour, the board is vertical (tokens can only be placed on top of other tokens) and winner is the player to first align four tokens of his color in a row.

The typical ConnectFour board has 7 columns and 6 rows, making it much smaller than a Go board. This is a benefit for our purposes: It means that the space of moves will be smaller and therefore the game will be easier to learn.

AlphaGo consists of several distinct components that it learned during it's training cycle:

- A model to determine who is most likely to win based on the current state of the board

- A model to predict what move an advanced player is likely to make

- A novel "policy" algorithm that combined these two to determine the best next move to make

For ConnectFour, I took a simplified approach and only trained the first of these models, which takes in the current board and predicts the likely winner. To build this model, I performed the following steps:

- Programmed the mechanics of the game so that I could simulate it

- Randomly played many games where two computer players picked random moves and end the game when one of them won

- Recorded the state of the board after every move and, for each move, noted who eventually won the game (or whether there was a tie)

- Used the positions of the boards across all games as training features and used the eventual winner as the target.

- Trained the first generation model using this data

Once I had a model to predict which player is more likely to win based on the state of the board, I used it to determine the best move to make based on the following policy:

- Consider all possible moves

- For each move, calculate the probability of winning after making the move

- Pick the move that leads to a board with the highest probability of winning

With the model and this strategy in hand, I used it to generate games for training data by having it play against itself many times. To increase the diversity of board positions seen, we actually used a somewhat less greedy policy than the one outlined above. When simulating games to generate training data, instead of always picking the best move, the strategy picked moves proportional to their relative probability of winning (which allows for sub-optimal moves to be occasionally picked). This generated additional training data that we mixed with our original random data and used to train a generation-2 model. And this process could be repeated multiple times, creating new generations, until the model achieves sufficient proficiency.

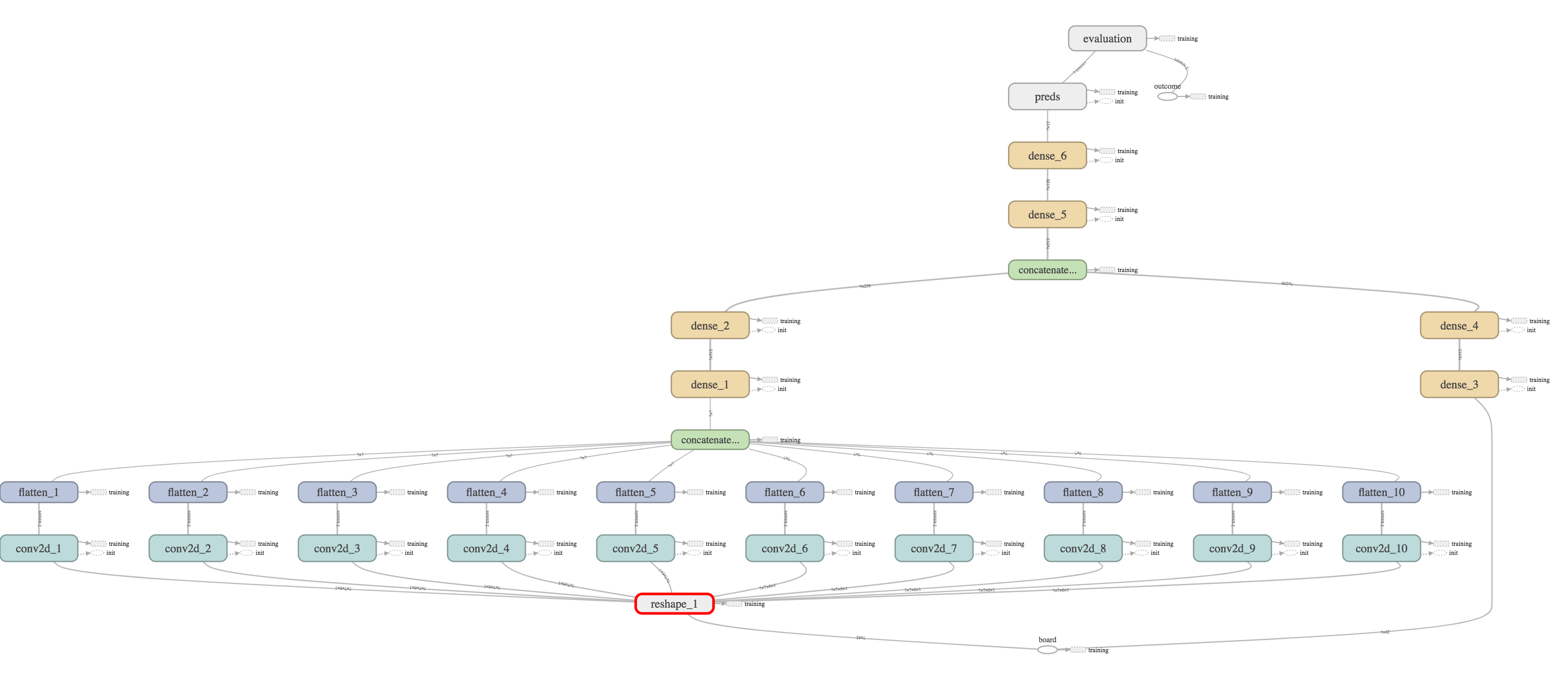

To train the board-position-to-win-probability model, I used neural networks built with Tensorflow. I experimented with a number of architectures, but ended up favoring one that leveraged both convolutional layers and dense fully-connected layers. Since the board is relatively small, using fully-connected dense layers wasn't prohibitive. To augment this, the convolutional layers were added to focus on small sub-sections of the board and identify specific patterns or possible moves that may lead to future success. For example, if a 4x1 convolution filter sees 3 pieces of the current player in a row and an empty place in the fourth position, it would be able to conclude with almost certainty that the current player will win (as it has a winning-move at hand). Doing this as a convolutional filter means that the network only needs to define this shape once and doesn't have to look at every possible combination of 4 consecutive spaces across the board.

The overall architecture included numerous convolution filters of this type (with different shapes and numbers of filers) as well as numerous fully connected layers. These layers were eventually connected via a fully-connected layer and fed into a SoftMax to determine the probability of win, lose, or draw. The network used RELU for all activation functions. I experimented with a number of permutations on this approach, including adding different types of regularization and trying alternate activation functions, most of which only had a small effect and led to decreased performance relative to our preferred architecture, which can be seen below:

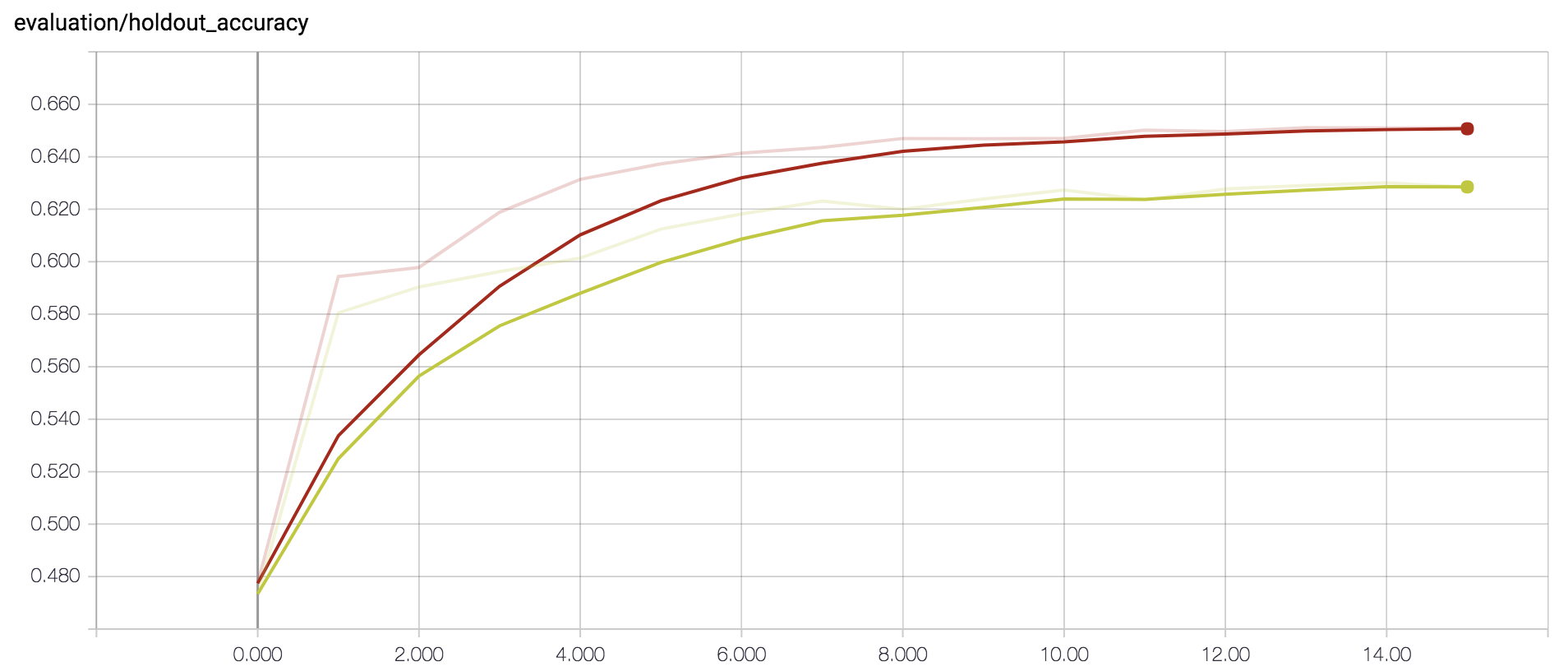

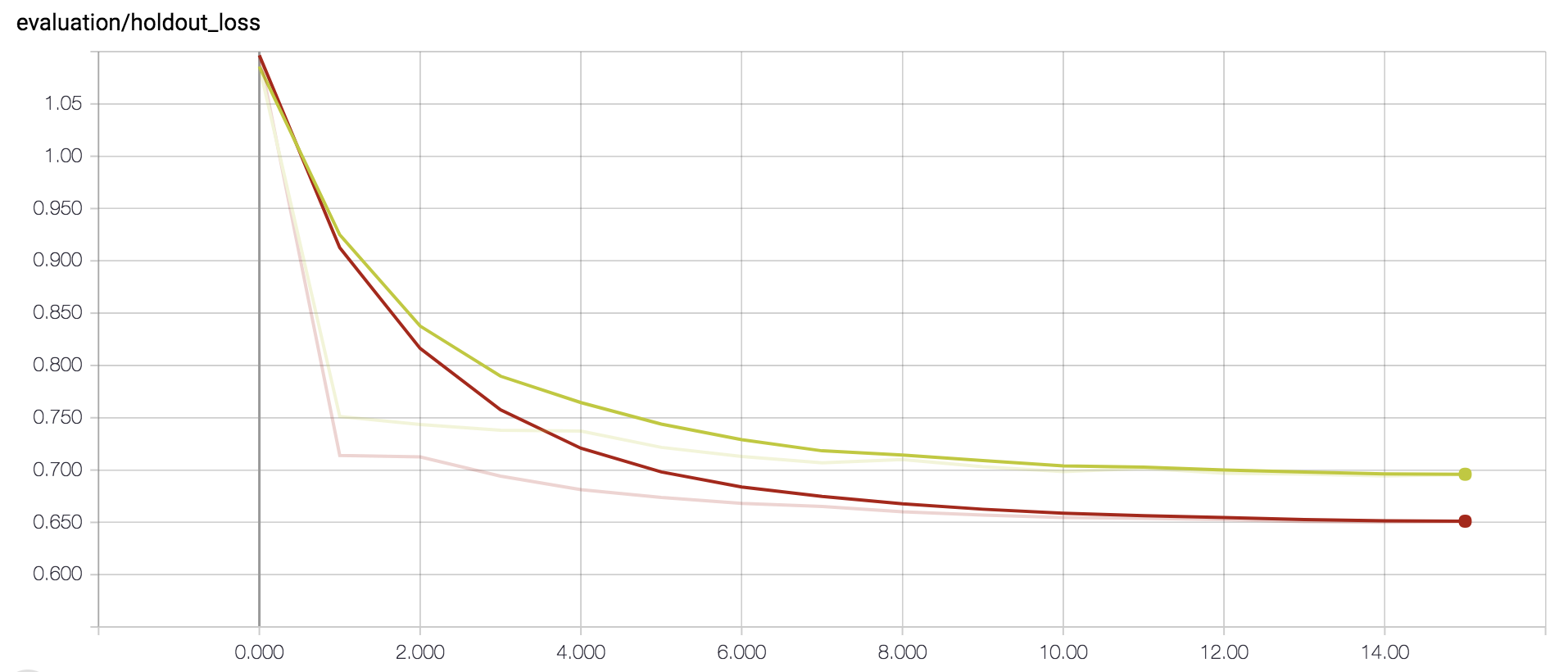

To fit the weights, I used the Adam optimizer and minimized the categorical cross-entropy using the softmax of the output predictions (which evaluates the accuracy of predicting win, lose, and draw). I also closely monitored the overall prediction accuracy during training as a proxy metric when evaluating the quality of the fit. I initially trained it on 500,000 randomly generated full games (leading to several million board positions) and added an additional 200,000 games using the bootstrapped AI.

I found that the overall accuracy increased as we moved from training on randomly-generated games to training on games between competent AIs. This makes sense, as the model predicts who will eventually win the game, and even with a good board position, a random player will have trouble exploiting it, but a skilled player will hold on to their advantage until victory.

And of course, having built the AI, I played against it. I'm not the most skilled ConnectFour player in the world, so it doesn't say too much that it was able to consistently beat me handedly. I was initially skeptical that this would work at all, so it was impressive to see it be able to put together what seemingly were multi-move combinations, leading to entrapping positions.

But the most impressive part was how conceptually easy it was to train this AI. I did nothing especially novel nor did we have to program in features or strategies related to the game itself. And I didn't have to have any specific knowledge of ConnectFour strategies. All we needed to do was program the rules and train (many) games, and the model was able to build off of that.

The code and scripts used to build and test these models can be found here