LHC Update:

Recently, there was an article in the New York Times that presented the prognosis of the LHC in a very negative light. To me, the timing of the article was somewhat arbitrary and the content was not in line with reality.

Last September, the Large Hadron Collider was “switched on” for the first time. Meaning, particles were injected into the main ring of the accelerator and caused to move through the machine. They were not collided nor did they reach their design energy. Nine days later, the machine broke.

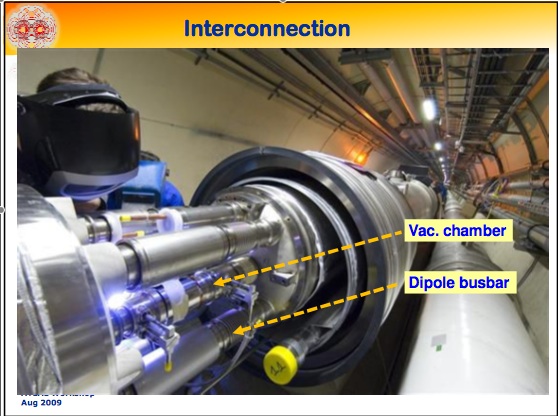

The problem occurred within the giant magnets, known as dipoles, that steer protons around the LHC ring. A connection between two such dipole magnets, due to heat produced from electrical friction, gained a much higher resistance than designed. When large current flows through large resistance, a lot of heat is produced. These connections are normally supercooled to a few degrees Kelvin using a large amount of helium and are designed to run at extremely small temperatures. The build up of heat within the electrical splice raised the temperature significantly beyond tolerance and caused a magnetic quench. In other words, the large amount of energy that is stored in the magnetic field, nearly 400 Mega Joules worth, was released in the form of electrical arcs, and these arcs punctured holes in the enclosure that stores the super-cold helium. This in turn caused a huge release of gas into a vacuum chamber. The gas expanded at an enormous rate, and the majority of the damage to the system during the incident was a direct result of quickly expanding helium.

The damage done by the incident of September 19th, 2008. The dipole magnet below isn't supposed to look like this:

In short, this was bad. Engineers have since examined the many other connections similar to the one that failed. They have put into place more detectors designed to give warning of the onset of high resistance within these splices, and have added many safety release valves to prevent catastrophic build up and release of pressure. Over the past year, many splices have been replaced, the dipole magnets have been fixed, and we are told that the machine will be able to function once again by November.

Several days ago, we were given the schedule of how the machine runs in early days. The LHC is designed to accelerate protons to 7 Terra Electron Volts (TeV), and when two collide, there is a total of 14 TeV in the center of mass available to create new particles. The LHC will not be able to achieve this energy right away. We learned this week that the LHC, after some initial calibrations, will run at 3.5 TeV per beam, meaning there will be a total of 7 TeV of energy when two particles collide.

To give a sense of scale, the largest particle collider that is not the LHC is the Tevatron. Located at Fermilab in Illinois, the Tevatron accelerates particles up to 1 TeV (hence its name) and they collide with 2 TeV available in the center of mass (the Tevatron differs from the LHC in that it collides protons with antiprotons. The LHC collides protons with other protons.)

So, even though the LHC will not reach its full potential in the next year or so, it will still be the most powerful particle accelerator in the world and will be able to probe physics far beyond the reach of the Tevatron. It is conceivable that we could see evidence of supersymmetry and extra dimensions using early data taken from these energies. However, it is extremely unlikely that we will be able to discover the Higgs Boson using this energy without several years worth of data taking. But whatever happens, the few months following the (second) turn on of the LHC in November should prove a very exciting time.